A friend casually left this for me to read—when I finally dove in I was shocked at the clarity and energy of Amy Liptrot’s writing. What a gem of a book. The revelations of her new found sobriety are woven into her explorations of the rough and wild Orkney islands.

Blog

Flea

I enjoyed the musician Flea’s new memoir, Acid for the Children—and amazed that he lived to tell the tale of his growing up in Hollywood, given the constant risks he took with leaps into pools from rooftops and needle drug use.

The style is offbeat, intelligent. Good for his editors to let him do it his way because it feels authentic, and very close to his heart, his truth. And it’s got that magic ingredient that makes it a compelling story.

So great to read how he was saved by music, access to instruments, musicians he met through his family and the freedom to try out different sounds, to listen to all kinds of music. Music was his path.

But he also talks about the books he read while growing up. It was his escape, and gave him big ideas, ways of looking at life beyond his family traumas, a structure he could climb into when his life was full violence and fear. Reading was his safe haven.

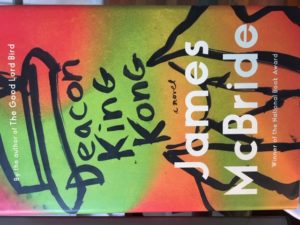

In this pandemic time, I am so hungry for books in that same way. They give me what I need—humor, peace, hope. Such a joy to read great sentences. I have recently read Deacon King Kong by James McBride. The sentences in that book! Long and lavish sentences that encompass individual feelings with the bigger world as it was. How have I not known about this fantastic writer? I was surprised and thrilled to read that he lives in New York City and Lambertville, New Jersey, where I grew up.

That’s it, just a praise note for reading, especially fiction.

Cousin Pons to the rescue

I was super excited to pick up three paperbacks at off-beat independent bookstores recently: The Dog of the South by Charles Portis, The Human Stain by Philip Roth and Cruising Paradise by Sam Shepard. I read the Roth book and did not like the plot or characters at all, but his writing style captured my attention. I bet he was never edited because he goes on and on. Anyway, since he died kind of recently, I wanted to remind myself why so many people think he’s great. I’m not a fan.

I like The Dog of the South mostly because it’s funny, but now that I’m further into it, the story is feeling superficial, as if it was written really fast. Only the Sam Shepard book is surviving my picky judgement. It’s got humor, good writing, unpredictable characters and … a lot of feeling.

In the middle of a recent hot Sunday, I wanted not just good but great writing to help me escape into another world, and I did not trust any modern writer to have this ability. So I turned to the shelf where I keep a lot of books from my parents’ house. These books are dusty and old, really old.

I pulled out Cousin Pons by De Balzac. Some people are crazy for him, so I opened it up.

Divine writing. Superb.

I’m swept up into the minute description of the curious clothing worn Sylvain Pons as he walks down the boulevard to the amusement of Parisian onlookers. This goes on for pages and it’s utterly compelling. I can’t break down the elements of this style, but I am so happy, and relieved, to be carried along by such a fine writer.

I will let you know how it holds up as I keep going, but something tells me it will.

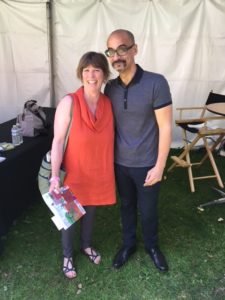

Junot Diaz

“Fools talk about diversity, but they can’t even imagine LA.” That was the first thing Junot Díaz said when he was introduced by LA Times writer Carolina Miranda at the LA Book Festival. It was just the beginning of a great hour-long talk.

I am sorry he’s disappeared from the landscape and hope it is temporary. He is too good a writer, and we can’t afford to lose his voice.

He is, of course, the author of the 2008 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. When I heard him at the book fesitval, I noticed that he could be measured and thoughtful, then suddenly urgent. He offered a political perspective about dictatorships one moment, then an intensely personal memory of being poor, the next. His mind is extraordinarily quick, and he fluidly shifted from English to Spanish and back again. He referred to his earthshaking piece in the New Yorker but did not want to discuss it as there were children in the audience.

He was there mostly to talk about his new children’s book Islandborn, with illustrations by Leo Espinoza. Again, I hope that this book gets the attention and audience that it deserves.

It’s about a little Afro-Caribbean girl named Lola who can’t remember the island where she was born because she was too little when she was brought to the U.S. by her parents. So she sets out to ask members of her extended family to describe the island so that she can “remember.” As they give her bits of information, she imagines for herself what these memories mean, adding her own whimsical interpretations. It’s a delightful story that feels very true to a child’s logic.

Díaz explained why it took him ten years to write the book — he didn’t want to be cute or to take shortcuts just because his audience would be children. How many writers are good enough to make those choices?

You have to be 100 percent faithful to the reader. So, his children’s book includes a monster—it comes up as a bad memory from one of the adults who’d left the island years before. In his talk, Díaz explained that the monster refers to the cruel dictator, Rafael Trujillo, who reigned for decades in the Dominican Republic.

In his exchanges with Carolina Miranda and audience members who asked questions, his compassion for writers, students and readers was evident. We need him.

Don’t write for free!

Would you ask a plumber to fix your toilet for free, just for the honor of coming into your house and being able to tell his friends that he worked for you? No. So why do so many people feel it’s fine to ask writers to write content for free? It’s not OK, and writers need to ask for, and receive, payment for their work.

One of my favorite writers, Naomi Hirahara, just posed a great FB post about why she does not write for free. She quotes another writer, Alexander Chee, who has written about this too. Both make such great points.

Chee says that a discussion about money must take place between the editor and the writer. And no matter what is offered, the writer must ask for more. No one should be embarrassed or insecure about talking about the terms of payment. Writers need to earn a living, and editors need to not take writers for granted, ever.

Another point that distresses me badly writers are getting paid less these days than in decades past. It’s just inexcusable. When budgets got slashed in publishing, fees for writers were the first to be reduced or cut. And except for rare instances, they have not been raised again. And that’s another reason why all writers (and I’m lecturing myself, here) need to ask for more money — not just for ourselves, but for all writers.

The need for happy endings

This is one of my dogs — her name is Lulu. She was found on Sunset Boulevard by three kind-hearted people who were on their way to dinner. They coaxed her off the street and told me later that she was completely black with dirt, and terrified. The deep scar on her snout and cuts on the sides of her gums indicated that her mouth had been wired shut for years.

By the time I met her, these kind people had given her a bath, had her seen by a vet and bought her a collar and an ID tag. My family and I fell in love with her and she’s been part of our family for about three years.

She’s got the good life at our house and is most beloved.

Such a good end of the story… and it’s a story I tell again and again, almost compulsively. Whenever asked about her by neighbors or other people we encounter on walks, I’m overly-eager to tell it.

I think it’s because Lulu’s story is so happy — and everyone craves happy endings. Craves them!

Happy endings help me to keep a toe-hold on hope, to remember that there is a lot of good in the world, in spite of appearances. But happy endings can become forced and false quickly, and the need for happy endings can cause story-tellers to leave out meaningful details of a character or a plot.

What I liked about the movie “Three Billboards…” was that right away the plot seemed to identify the good and bad characters, and then slowly those roles dissolved. The good ones were not so good, and the bad ones were not so bad. And… there was no real happy ending. The book Atonement by Ian McEwan totally played with the readers’ desire for a happy ending, which propelled the drama.

I like noir books and films. I also like sarcasm when it’s matched with good wit. To leave out darkness is a mistake for writers, a death knell for novels.

Yet, happy endings, when they really do happen, can seem miraculous, especially when I’ve decided the world really has gone to hell.

So, just to let you know: It’s 3 p.m. on a warm afternoon in Los Angeles, and Lulu is asleep on our back porch, partly in the sunshine, partly in the shade. Her little stomach rises and falls with her naptime breathing. She looks pretty happy.

Violence in novels

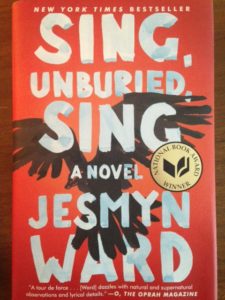

I recently read Sing, Unburied, Sing, the latest novel by Jesmyn Ward. She is a first-rate writer and this book is a gem. But I won’t count it among my favorites because of the graphic violence it contains (there’s also a lot of vomiting).

I recently read Sing, Unburied, Sing, the latest novel by Jesmyn Ward. She is a first-rate writer and this book is a gem. But I won’t count it among my favorites because of the graphic violence it contains (there’s also a lot of vomiting).

I’m not one who believes that a novel is more authentic or truthful if it contains violence that is particularly graphic. I understand of course when it’s part of a reality, and I don’t want to deny it’s existence or effect, but no, I don’t want to fill my soul with its images. I am far more intrigued and drawn in by a novel that has unexpected plot twists, dimensional characters, and drama—all of which Sing, Unburied, Sing has also by the way.

I don’t enjoy reading about cruelty or physical harm that people do to each other, especially when it isn’t essential to the plot or leads to no redemption. I’m thinking of The Girls by Emma Cline, a novel I really dislike (though I do like her short stories). There is so much real violence in the world, I don’t want to immerse myself in it with a book.

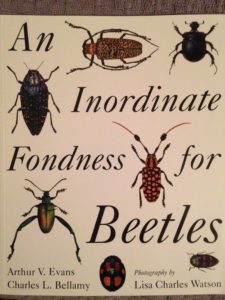

Go ahead, judge books by their covers

I judge books by their covers — who doesn’t, really? I fell in love with this cover and the book has lived up to its promise. It makes the subject of these creepy things totally fascinating.

Sentences like this intrigue me, whether I understand the material or not: “Beetles consume everything—plants, animals, and their remains. Larvae and adults are found in the soil, where they function as tiny recycling machines that return organic materials to the soil, making them available again for use by plants and other animals.”

I see people reading everywhere—my method for gauging the state of publishing. My favorite sight is that of a person walking and reading at the same time (but somehow seeing people walking and texting just makes me feel sad).

Here’s another book cover I love, Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man. First few sentences: “I was leaning against the bar in a speakeasy on Fifth-second Street, waiting for Nora to finish her Christmas shopping, when a girl got up from the table where she had been sitting with three other people and came over to me. She was small and blonde, and whether you looked at her face or at her body in powder-blue sports clothes, the result was satisfactory. “Aren’t you Nick Charles?” she asked.

I said: “Yes.”

Reading protects my brain by orienting my thinking to the long narrative, rather than scattering my concentration which is what happens when I spend time on social media. Following a good novel’s story path allows me to relax into a multi-layered tale that triggers feelings from the past and present, and challenges my mind to make sense of it all. I love that.

Some people love curling up with a Kindle, but I’m not one of them. I like a book I can slip into my bag, lend to a friend, keep on my bedside table, read when I have a moment in the early morning or late at night. And if I’m too tired to read, I can just gaze at the cover.